- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

“Why in Seattle?” a reporter asked Ai Weiwei at the press conference.

“Why not?!” he answered.

This brief interaction stayed with me no less profoundly than the aura of the actual works representing Ai’s decades-long activism. A few weeks later, I began to demystify that “why not?!”: it could be only a matter of time before the sociopolitical climate changes dramatically even in the most liberal corners of the world, such as Seattle. In that sense, refreshing our collective memory through projects that expose the many forms of power abuse is, at the very least, something we should do.

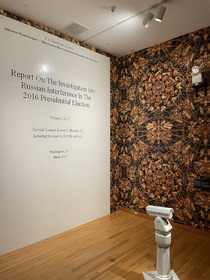

This overtly political emphasis seemed to be on the mind of curator Foong Ping as well. After all, the exhibition culminated in a monumental mural made of Lego bricks depicting the cover page of Robert Mueller’s Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election. Strikingly, the mural was mounted on a wallpaper featuring a dense bundle of surveillance cameras rendered in an opulent baroque style—an aesthetic choice that subtly echoed the tastes of the nouveau riche and the visual culture of oligarchic power. The report itself encompasses Mueller’s findings on Russia’s efforts to influence the 2016 US presidential election. As a result, the conventional format of retrospective exhibitions was challenged: the visitor’s final impression, arguably, would not be rooted in the artist per se, but rather in a political discourse that centered the United States itself.

In contrast to the exhibition’s climactic ending, the work greeting visitors at the entrance transcended immediate political concerns and confronted something more primal: the capriciousness of human action. Specifically, the show began with Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), a photo triptych depicting Ai smashing an ancient vessel. The performance was documented by the artist’s brother, Ai Dan, who was testing his new Nikon F3 camera; as soon as it ended, the brothers swiftly disposed of the shards before their mother could see. Both the artwork and its label introduced visitors to key themes in Ai’s practice—spontaneity, simplicity, immateriality and detachment, irony and naivety—offering a visceral experience for 21st-century viewers overwhelmed by constant streams of images, texts, and shifting values.

Smashing an urn uncovered one of the exhibition’s fundamental layers: the necessity of relinquishing the old. In this, it echoed a key Weiweism: “We need to get out of the old language.” A series of works further explored this idea through diverse forms. Porcelain Pillar with Refugee Motifs (2017), as its title suggests, depicted the tragedies of displacement using the traditional cobalt blue paint associated with classic Chinese porcelain. Beyond its central message, to me, the work questioned the classical view of traditional artifacts as purely apolitical and raised concerns that the ongoing reproduction of established patterns could sometimes feel limiting or backward-looking. In the neighboring hall, visitors confronted the idea of the “obsolete old” through a series of unergonomic furniture—whether a table balanced with two legs on the floor and two against the wall, a bundle of chairs, or a marble sofa. Yet, within this collection, the visitor was invited to consider the innovative potential hidden within these morbid, dysfunctional objects, thereby echoing Antonio Gramsci’s paradigm of a world “where the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” The climax of this exploration came with the iconic Han Jar Overpainted with Coca-Cola Logo (1995), a work that dramatized the distortion and exploitation of the old. Here, capitalism acts as a parasite, refusing to let the old truly die. This juxtaposition of Pop Art with deeply traditional forms further mirrored Ai’s biographical currents, stretched between the Western hemisphere and China, where, despite their differences, both capitalism and corporatist socialism feed off each other.

Repetition seems to be another method Ai employs to impress, inform, and affect the viewer. I could identify three forms of repetition in his portfolio. First, we have citations: not only does the previously mentioned jar allude to Andy Warhol’s legacy, but the portraits of Mao Zedong from the 1980s also repeat the visual aesthetics of a totalitarian Social Realism. Then, there is Mao 1-3, a 1986 triptych. While some interpret it as inspired again by Warhol’s portraiture of the Chinese dictator, to me it evokes Francis Bacon’s mid-century depictions of individuals left with nothing but absorption and decay. And there are literal configurations of repetition as well. This approach is best epitomized by the Sunflower Seeds project, first unveiled at Tate Modern in 2010 and later showcased in fragments throughout various exhibitions, including the current one.

The most striking example of repetitive method, however, was the serpentine installation of the Remembering project, first realized in Munich in 2009. Extending across multiple galleries, visitors initially had no prior knowledge of the work’s concept; only later would they learn that the line of bags suspended from the ceiling represents the tens of thousands of victims of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, most of whom were school children. This tragedy is further memorialized by a monumental inkjet print listing the names of the victimized students. As the label states, “Visualized here in a terribly long list, the names and details of these 5,197 individuals make the scale of the casualties impossible to deny and ensure that the circumstances leading to their death will be forgotten.” Paradoxically, this memorial sparked an opposite reflection in me: despite each victim being identified by name, it also reveals a misfortune of the modern world—seeing humans as mere numbers, subjects reduced to statistics. Thus, Ai’s catalog of tragedies simultaneously echoed to me the malpractice of those in power who treat individuals not as unique beings but as mere IDs—entities that follow specific trends, whose behavior can be predicted and manipulated, so much so that data scientists might even forecast who will be the next president or flag individuals as potential dissenters before they act, echoing the logic of surveillance regimes the artist has long opposed.

Finally, we encounter a third mode of repetition in Ai Weiwei’s practice—one rooted not in citation or configuration, but in the material particles of the medium itself, which, more often than not, take the form of a simple Lego brick. In addition to the epic Mueller Report piece discussed above, a separate gallery hosted a number of large-scale Lego murals, but it was specifically Ai’s 2022 Water Lilies that expanded Ai Rebel to the new venue.

The work’s presence at the Asian Art Museum seems justified by historical resonance: it recalls the controversy surrounding Walter P. Chrysler’s collection, which formed The Great Exhibition at Seattle Art Museum in 1956 and included Claude Monet’s Water Lilies. As was later revealed (with the help of a critical note from Pablo Picasso), Chrysler’s collection—due to his rapid and sometimes indiscriminate acquisitions—allegedly included forgeries. While Ai’s piece is rooted in his father Ai Qing’s memories of Paris and the Impressionists, Water Lilies ultimately questions the notion of truth itself—what makes something “authentic,” and do we sanction fakeness if it delivers beauty? In doing so, Ai probes the negotiated—and often unstable—nature of aesthetic experience, yet his Lilies ultimately affirm a notion of beauty akin to that of Thomas Aquinas: “pulchra enim dicuntur quae visa placent” (Those things are beautiful which, when seen, please).

Nevertheless, while spending some time in front of monumental 105 ½ x 602 ¾ inch work, reason seems to strike back, and one starts to wander: is this more than a citation of Monet? Doesn’t it resemble a political map? What if the distribution of colors signals the world’s most politically turbulent zones? And what are we to make of the dark spot—what Ai himself equates with the cave, a space he has described as where his family lived in exile—which, to me, evokes not only “enforced sanctuary” but also a black hole, a void that threatens the viewer with the seductive idea of negotiated comfort in the hidden? One continues to scan for political meaning—as if inevitably compelled to do so. After all, it is Ai himself who reminds us with another Weiweism: “Everything is art. Everything is politics.”

Interpretative speculations may be infinite, but to me, this work positions politics on a meta-level, once again entwined with the idea of beauty. Does the seductive surface of this mural enact the kind of charm that turns our gaze away from the world’s urgencies? Or does it ask us to confront a deeper truth about beauty—one that transcends conventional categories of good and evil? After all, are not the greatest horrors often wrapped in a disarming aesthetic, one that either makes us complicit or simply stunned into passivity?

Nikoloz Nadirashvili

PhD Student, Art History Department, University of Washington